Augmenting the Creativity of A Child with A.I.

The details behind my most recent painting are complex, but the impact is simple.

My robots had a photoshoot with my youngest child, then painted a portrait with her in the style of one of her paintings. Straightforward A.I. by today’s standards, but who really cares how simple the process behind something is as long as the final results are emotionally relevant.

With this painting there were giggles as she painted alongside my robot and an amazed result when she saw the final piece develop over time, so it was a success.

The following image shows the inputs, my robot’s favorite photo from the shoot (top left) and a painting made by her (top middle). The A.I. then created a CNN style transfer to reimagine her face in the style of her painting (top right). As the robot worked on painting this image with feedback loops, she painted along on a touchscreen, giving the robot direction on how to create the strokes (bottom left). The robot then used her collaborative input, a variety of generative A.I., Deep Learning, and Feedback Loops to finish the painting one brushstroke at a time (bottom right).

In essence, the robot was using a brush to remove the difference between an image that was dynamically changing in its memory with what it saw emerging on the canvas. A timelapse of the painting as it was being created is below…

Pindar

Visions - Five Minute Piece on My Robot's Latest AI

Click on image or here to see recent piece about my robot's latest AI and how it uses artificial creativity to paint...

Pindar

Channelling Picasso and Braque

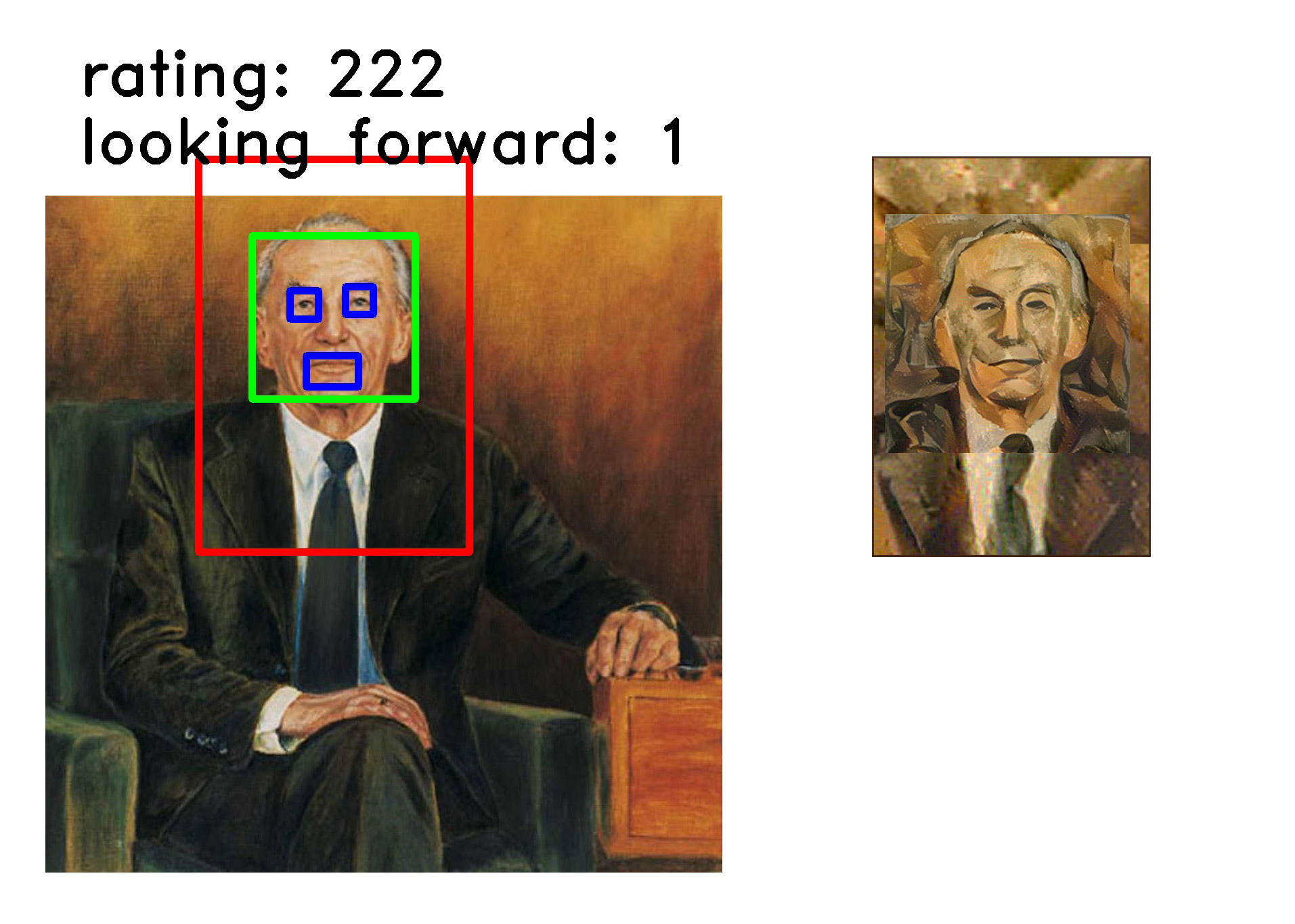

My latest robotic painting commission (seen above) began with a question and a challenge.

I was sent a couple portraits and several cubist works and asked

“whether style transfer works better or whether there are other ways of training the algorithm to repaint a picture analytically in a similar way that Picasso and Braque did when they started (i.e. dissecting a picture into basic geometrical shapes, getting more abstract with every round, etc.).”

It seemed obvious to me that the analytical approach would be better, if only for the reason that that was what the original artists had done. But I wasn’t sure and experimenting with this question sounded like a wonderful idea, so I dived into the portrait. I began by first using style transfer to make a grid of portraits as reimagined by neural networks.

The results were as could be expected, but regardless I always find it amazing how well cubist work lends itself to Style Transfer. This process works for some art styles and completely fails on others, but I have always found that it is particularly well suited for cubism.

With several style transfers completed, I began experimenting with a more analytical approach. The first process I began was to use hough lines to attempt to find lines and therefore shapes from both the original portraits and the neural network imagined ones.

The image above shows many of the attempts to find and define line patterns in both the original portraits and the cubist style transfers. I was expecting better results, but the information was at least useful…

It showed me which of the original six cubist style transfers had the most defined shapes and lines (right). It also gave my robots a frame of reference for how to paint their strokes when the time would come.

I was a little stumped though. I had expected better results, and my plan was to use those results to determine the path forward. I thought I could perhaps find shapes in the images, and then use the shapes to draw other shapes to create abstract portraits. But those shapes did not materialize from my algorithms. Frustrated and wondering where to go next, I put the images through many of my traditional AI algorithms including the viola-jones facial detection algorithm and some of my own beauty measuring processes.

My robots gathered and and studied hundreds of images using a variety of criteria. In the end it settled on the following composition and style. The major deciding factor for going with this composition was that it found it to be the most aesthetically pleasing of every variation it tested. The reason it picked the style was that it was the style that produced the richest set of analytical data. For example, the hough lines performed in the previous processes revealed more lines and shapes in this particular Picasso than any of the other style transfers. I expected that this would be useful later on in the process.

At this point I wanted to go forward but was still unsure of how to proceed. Fortunately artists have a time honored trick when they do not know what to do next. We just start painting. So I loaded all the models into one of my large format robots and set it to work. I figured the answer to what to do next would emerge as the painting was being made.

As the robot painted for a about a day, it did not make many aesthetic decisions. It just painted the general texture and shading of the portrait taking direction from the hough lines. As I was waiting for this sketch to finish, a second suggestion came from the commissioner of the portrait. I was asked:

“What if we tried to run a standard photo morphing process from one of the faces of the classical cubist work and see whether an interim-stage picture of this process could be a basis for the AI to work from?”

I had never done this before and it was an interesting thought so I gave it a shot. I found the results intriguing. Furthermore, it was fun to see the exact point in the morphing process at which the likeness disappears, and the face becomes a Braque painting.

Another interesting aspect of creating the morphing animation was that I was able to compare it to an animation of how the neural networks applied style transfer. For the comparison, both animation can be seen to the left.

Interesting comparison aside, I had a path forward. I showed my robots how to use the morphed image. For the second stage of the painting they worked towards completing the portrait in the style of a Braque.

I was really liking the results, however, there was one major problem. The portrait was too abstract. It no longer resembled the subject of the portrait. It had lost the likeness, and the one thing that every portrait should do is resemble the subject, at least a little. This portrait didn’t and I realized it needed another round to bring the likeness back.

To accomplish this I had the robot use both another round of style transfer and morphing to return to something that better resembled the original portrait. The robot had gone too abstract, so I was telling it to be more representational.

While the style transfer at this stage was automatic, the morphing required manual input from me. I had to define the edges of the various features in both the source abstract image and the style image. I tried to automate this step, but none of my algorithms could make enough sense of the abstract image. It didn’t know how to define things such as the background or location of the eyes. I will work on better approaches in the future, but for now I do not find it surprising that this is a weakness of my robot’s computer vision.

The final painting was completed over the course of a week by my largest robot. Below is a timelapse video of its completion…

The description I just gave about how my robots produced this has been an abbreviated outline of my entire generative AI art system. Several other algorithms and computer vision systems were used though I really only concentrated on describing the back and forth between Style Transfer and Morphing. The robot began by using neural networks to produce something in the style of a cubist Picasso, then morphed the image to imitate a Braque. Once things had gone too abstract, it finished by using both techniques to return to a more representational portrait. Back and forth and back again.

After the robot had completed the 12,382 strokes seen in the video, I touched it up by hand for a couple of minutes before applying a clear varnish. It is always relieving that while my robots can easily complete 99.9% of the thousands of strokes it applies, I am still needed for the final 0.1%. My job as an artists remains safe for now.

Pindar Van Arman

cloudpainter.com

AI as a Creative Tool - Art with the Assistance of Painting Robots

"AI as a Creative Tool - Art with the Assistance of Painting Robots" is what I am calling my recent talk at the Aspen Institute in Berlin. Just finished editing footage of the talk to include my slides. Enjoy...

Pindar

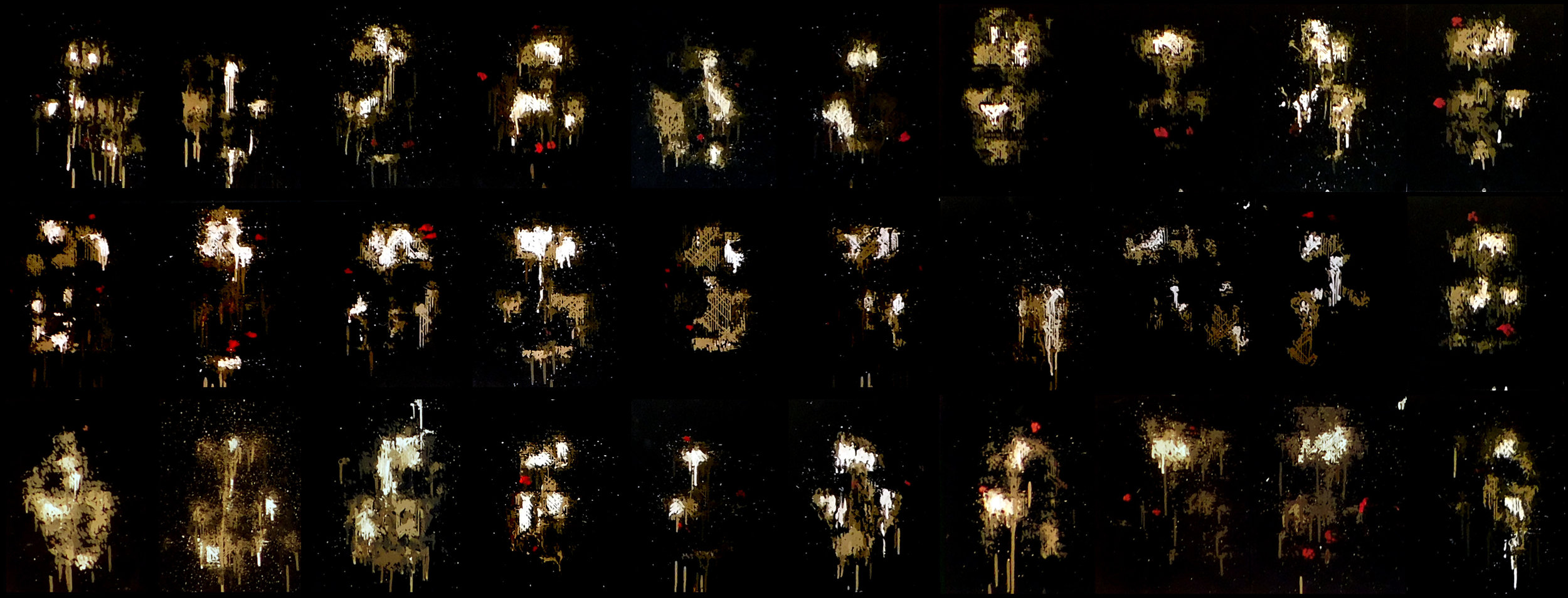

More Ghostlike Faces Imagined by my Robots

My series of portraits painted by my robot continues with these 32 ghost images. Calling the series Emerging Faces. Will be discussing how and why my robots are thinking these up and painting them in Korea next week. Will post a more detailed account here shortly. Here are some closer looks at some of my favorite images...

Pindar

The First Sparks of Artificial Creativity

My robots paint with dozens of AI algorithms all constantly fighting for control. I imagine that our own brains are similar and often think of Minsky's Society of Minds. Where he theorizes our brains are not one mind, but many, all working with, for, and against each other. This has always been an interesting concept and model for creativity for me. Much of my art is trying to create this mish mosh of creative capsules all fighting against one another for control of an artificially creative process.

Some of my robots' creative capsules are traditional AI. They use k-means clustering for palette reduction, viola-jones for facial recognition, hough lines to help plan stroke paths, among many others. On top of that there are some algorithms that I have written myself to do things like try to measure beauty and create unique compositions. But the really interesting stuff that I am working with uses neural networks. And the more I use neural networks, the more I see parallels between how these artificial neurons generate images and how my own imagination does.

Recently I have seen an interesting similarity between how a specific type of neural network called a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) imagines unique faces compared to how my own mind does. Working and experimenting with it, I am coming closer and closer to thinking that this algorithm might just be a part of the initial phases of imagination, the first sparks of creativity. Full disclosure before I go on, I say this as an artist exploring artificial creativity. So please regard any parallels I find as an artist's take on the subject. What exactly is happening in our minds would fall under the expertise of a neuroscientist and modeling what is happening falls in the realm of computational neuroscience, both of which I dabble in, but am by no means an expert.

Now that I have made clear my level of expertise (or lack thereof), there is actually an interesting thought experiment that I have come up with that helps illustrate the similarities I am seeing between how we imagine faces compared to how GANs do. For this thought experiment I am going to ask you to imagine a familiar face, then I am going to ask you to get creative and imagine an unfamiliar face. I will then show you how GANs "imagine" faces. You will then be able to compare what went on in your own head with what went on in the artificial neural network and decide for yourself if there are any similarities.

Simple Mental Task - Imagine a Face

So the first simple mental task is to imagine the face of a loved one. Clear your mind and imagine a blank black space. Now pull an image of your loved out of the darkness until you can imagine a picture of them in your mind's eye. Take a mental snapshot.

Creative Mental Task - Imagine an Unfamiliar Face

The second task is to do the exact same thing, but by imagining someone you have never seen before. This is the creative twist. I want you to try to imagine a face you have never seen. Once again begin by clearing your mind until there is nothing. Then out of the darkness try to pull up an image of someone you have never seen before. Take a second mental snapshot.

This may have seemed harder, but we do it all the time when we do things like imagine what the characters of a novel might look like, or when we imagine the face of someone we talk to on the phone with, but have yet to meet. We are somehow generating these images in our mind, though it is not clear how because it happens so fast.

How Neural Nets Imagine Unfamiliar Faces

So now that you have tried to imagine an unfamiliar face, it is neat to see how neural networks try to do this. One of the most interesting methods involves the GANs I have been telling you about. GANs are actually two neural nets competing against one another, in this case to create images of unique faces from nothing. But before I can explain how two neural nets can imagine a face, I probably have to give a quick primer on what exactly a neural net is.

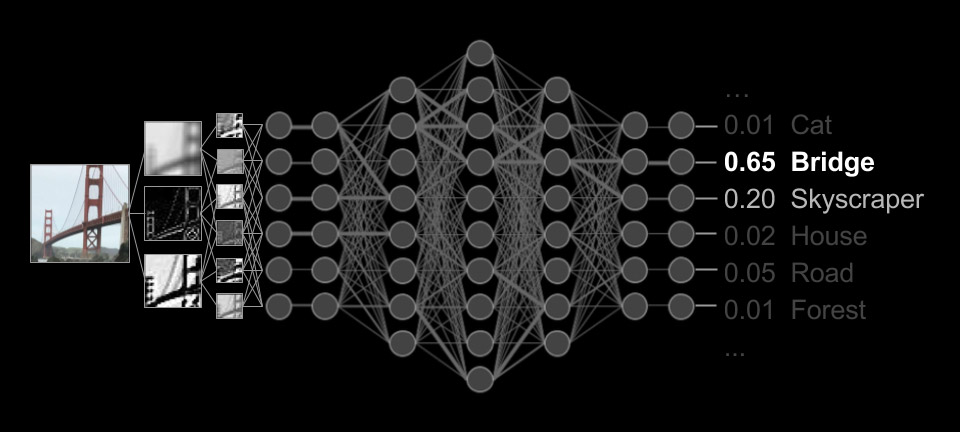

The simplest way to think about an artificial neural network is to compare it to our brain activity. The following images show actual footage of live neuronal activity in our brain (left) compared to numbers cascading through an artificial neural network (right).

Live Neuronal Activity - courtesy of Michelle Kuykendal & Gareth Guvanasen

Artificial Neural Network

Our brains are a collection of more than a billion neurons with trillions of synapses. The firing of the neurons seen in the image on the left and the cascading of electrical impulses between them is basically responsible for everything we experience, every pattern we notice, and every prediction our brain makes.

The small artificial neural networks shown on the right is a mathematical model of this brain activity. To be clear it is not a model of all brain activity, that is computational neuroscience and much more complex, but it is a simple model of at least one type of brain activity. This artificial neural network in particular, is small collection of 50 artificial neurons with 268 artificial synapses where each artificial neuron is a mathematical function and each artificial synapses is a weighted value. These neural nets simulate neuronal activity by sending numbers through the matrix of connections converting one set of numbers to another. These numbers cascade through the artificial neural net similarly to how electrical impulses cascade through our minds. In the animation on the right, instead of showing the numbers cascading, I have shown the nodes and edges lighting up and when the numbers are represented like this, one can see the similarities between live neuronal activity and artificial neural networks.

While it may seem abstract to think how this could work, the following graphic shows one if its popular applications. In this convolutional neural network an image is converted into pixel values, these numbers then enter the artificial neural network on one side, go through a lot of linear algebra, and eventually comes out the other side as a classification. In this example, an image of a bridge is identified as a bridge with 65% certainty.

With this quick neural network primer, it is now interesting to go into more details of a face creating Generative Adversarial Network, which is two opposing neural nets. When these neural nets are configured just right, they can be pretty creative. Furthermore, closely examining how they work, I can't help but wonder if some structure similar to them is in our minds at the very beginning of when we try to imagine unfamiliar faces.

So here is how these adversarial neural nets fight against each other to generate faces from nothing.

The first of the two neural nets is called a Discriminator and it has been shown thousands of faces and understands the patterns found in typical faces. This neural net would master the first simple mental task I gave you. Same as how you could pull the face of a loved one into your imagination, this neural net knows what thousands of faces looks like. Perhaps more importantly, however, when shown a new image, it can tell you whether or not that image is a face. This is the Discriminator's most important task in a GAN. It can discriminate between images of faces and images that are not faces, and also give some hints as to why it made that determination.

The second neural nets in a GAN is called a Generator. And while the Discriminator knows what thousands of faces looks like, this Generator is dumb as a bag of hammers. It doesn't know anything. It begins as a matrix of completely random numbers.

So here they are at the very beginning of the process ready to start imagining faces.

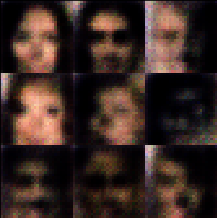

First thing that happens is the Generator guesses at what a face looks like and asks the Discriminator if it thinks the image is a faces or not. But remember the Generator is completely naive and filled with random weights, so it begins by creating an image of random junk.

When determining whether or not this is a face, the Discriminator is obviously not fooled. The image looks nothing like faces. So it tells the Generator that the image looks nothing like faces, but at the same time give some hints about how to makes its next attempt a little more facelike. This is one of the really important steps. Beyond just telling the Generator that it failed to make a face, the Discriminator is also telling it what parts of the image worked, and the Generator is taking this input and changing itself before making the next attempt.

The Generator adjusts the weights of its neural network and 120 tries, rejections, and hints from the Discriminator later, it is still just static, but better static...

But then at attempt 200. ghosts images start to emerge out of the darkness...

and with each guess by the Generator, the images get more and more facelike...

at attempt 400,

600,

1500,

and 4000.

After 4,000 attempts, rejections, and corrections from the Discriminator, the Generator actually gets pretty good at making some pretty convincing faces. Here is an animation from the very first attempt to the 4,000th iteration in 10 seconds. Keep in mind that the Generator has never seen or been shown a face.

So How Does this Compare to How We Imagined Faces?

Early on we did the thought experiment and I told you that there would be similarities between how this GAN imagined faces and you did. Well hopefully the above animation is not how you imagined an unfamiliar faces. If it was, well, you are probably a robot. Humans don't think like this, at least I don't.

But let's slow things down and look at what happened with the early guessing (between the Generators 180th and 400th attempts).

This animation starts with darkness as nondescript faces slowly bubble out of nothing. They merge into one another, never taking on a full identity.

I am not saying that this was the entirety of my creative process. Nor am I saying this is how the human brain generates images, though I am curious what a neuroscientist would think about this. But when I tried to imagine an unfamiliar face, I cleared my mind and an image appeared from nothing. Even though it happens fast and I can not figure out the mechanisms doing it, it has to start forming from something. This leads me to wonder if a GAN or some similar structure in my mind began by comparing random thoughts in one part of my mind to my memory of how all my friends look in another part. I wonder if from this comparison my brain was able to bring an image out of nothing and into vague blurry fog, just like in this animation.

I think this is the third time that I am making the disclaimer that I am not a neuroscientist and do not know what exactly is happening in my mind. I wonder if any neuroscientist does actually. But I do know that our brains, like my painting robots, have many different ways of performing tasks and being creative. GANs are by no means the only way, or even the most important part of artificial creativity, but looking at it as an artist, it is a convincing model for how imagination might be getting its first sparks of inspiration. This model applies to all manner of creative tasks beyond painting. It might be how we first start imagining a new tune, or even come up with a new poem. We start with base knowledge, try to come up with random creative thoughts, compare those to our base knowledge, and adjust as needed over and over again. Isn't this creativity? And if this is creativity, GANs are an interesting model of the very first steps.

I will leave you here with a series of GAN inspired paintings where my robots have painted the ghostlike faces just as they were emerging from the darkness...

Emerging Faces, 110"x42", Acrylic on Canvas, Pindar Van Arman w/ CloudPainter

Pindar

Converting Art to Data

There is something gross about breaking a masterpiece down into statistics, but there is also something profoundly beautiful about it.

Reproduced Cezanne's Houses at the L'Estaque with one of my painting robots using a combination of AI and personal collaboration. One of the neat things about using the robot in these recreations, is that it saves each and every brush stroke. I can then go back and analyze the statistics behind the recreation. Here are some quick visualizations...

It is weird to think of something as emotional as art, as data. But the more I work with combining the arts with artificial intelligence, the more I am beginning to think that everything is data.

Below is the finished painting and an animation of each brush stroke.

Can robots be creative? They Probably Already Are...

In this video I demonstrate many of the algorithms and approaches I have programmed into my painting robots in an attempt to give them creative autonomy. I hope to demonstrate that it is no longer a question of whether machines can be creative, but only a debate of whether their creations can be considered art.

So can robot's make art?

Probably not.

Can robots be creative?

Probably, and in the artistic discipline of portraiture, they are already very close to human parity.

Pindar Van Arman

TensorFlow Dev Summit 2017

About two months ago I applied to go to Google's first annual TensorFlow Dev Summit. I sent in the application and forgot about it. After a month I figured that I did not get an invite. Then about a week ago, the invite came in. Turns out only one in ten applicants were invited to the conference. I have no idea what criteria they used to select me, but I am currently on plane to Mountain View excited to talk with the TensorFlow team and see what other developers are doing with it.

The summit will be broadcast live around the world. Here is a link. Look for me in the crowd. I will have a grey pullover on.